|

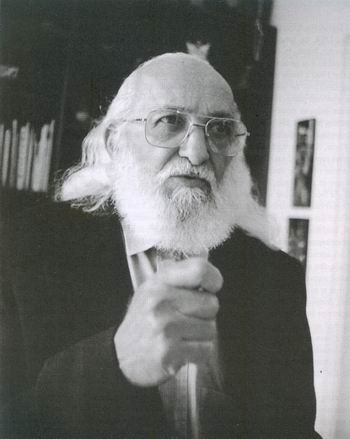

Paulo Freire, courtesy Paulo Freire Institute

Critique of the Teacher- Student

Relationship in the "Banking"

Concept of

Education

Introduction

At the very least, education implies change. At its highest, education implies rapid

evolution, revolution or transmutation. The greater the perception of present

inadequacies and imperfections, the greater the spur for radical change or

transmutation. The stage through which we are passing in human history is marked

by crises in which the perception of human inadequacies becomes increasingly

acute. We are dissatisfied with ourselves, both individually and collectively. If we

define justice as Plato did, as a state in which everyone occupies his proper place in

a social organization, then the whole world is in a state of injustice. Things, events,

and men are not where they ought to be. In such circumstances, education must be

^ a process of total revolution and transmutation.

Education is fundamentally what takes place in the body, mind and heart of the

pupil; what happens in the pupil depends largely on the teacher-pupil relationship;

this relationship determines and is determined by the educational system; and the

educational system is overwhelmingly determined by the economic, social and

cultural relations in human society. An imperfect society cannot hope to provide a just

educational system, right relationships between teacher and pupil and valid

pedagogical processes. It is equally true that imperfect human beings cannot create a

perfect society, and so long as human beings continue to remain within the narrow

grooves of their present limited consciousness, we cannot hope to create a just society.

The revolutionary process, therefore, must operate both within the educational system

Page-491

and outside it. An awakened teacher and an awakened pupil can participate in this

revolution by revolutionizing their own relationships and processes of teaching and learning.

There is widespread oppression in the world. It aims at conquest; its methods

of action are manipulative; it invades individuals and groups and inhibits creativity

and expression. Oppression aims at preserving itself; it perpetuates the division of

the oppressor and the oppressed; it resists any revolutionary movement advocating

dialogue, co-operation, unity, humanization, and spiritualization. In the teaching-

learning process, oppression tends to perpetuate the status quo. It advises teachers

to teach and pupils to learn, while opposing the processes of education where

teachers become learners and where students can teach their own teachers. It

opposes the dialogic character of the teaching-learning process.

Paulo Freire's book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, is a stimulating exposition of

the phenomenon of oppression in our educational system and society and the

manner in which this oppressive action can be reversed and defeated. Freire

criticizes the present concept of education, calling it the "banking concept", where

knowledge is a gift bestowed by those considered knowledgeable upon those who are

not. "Banking" education regards men as adaptable, manageable beings and

minimizes or annuls the creative power of pupils. It reacts almost instinctively

against any educational experiment which stimulates the critical faculties. Freire

points out that oppressors manifest interest in changing the consciousness of the

oppressed, but not the oppressive situation itself.

The educator's role in "banking" education is to regulate the way the world

"enters into " the student, to "fill" the students with deposits of information considered

as true knowledge. "Banking" education is "necrophilous" a word which Freire

explains by quoting the following passage from Erich Fromm' s The Heart of Man:

While life is characterized by growth in a structured, functional manner, the

necrophilous person loves all that does not grow, all that is mechanical. The

necrophilous person is driven by the desire to transform the organic into the inorganic,

to approach life mechanically, as if all living persons were things.... Memory, rather

than experience; having, rather than being, is what counts. The necrophilous person

can relate to an object a flower or a person only if he possesses it; hence a threat

to his possession is a threat to himself; if he loses possession he loses contact with the

world.... He loves control, and in the act of controlling he kills life.1

1, Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985), pp. 50-51.

Page-492

The process of humanization, on the other hand, is a process of liberation, and

authentic liberation is not merely another "deposit" to be made in men.

Freire says, "Liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men upon their

world in order to transform it. Those truly committed to the cause of liberation can

accept neither the mechanistic concept of consciousness as an empty vessel to be

filled, nor the use of banking methods of domination (propaganda, slogans

deposits) in the name of liberation. "1

Freire advocates "problem-posing" education, the creation of dialogic

relations between teachers and pupils. He says, "Through dialogue, the teacher-of-

the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges:

teacher-student with students-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-

who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in

their turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a

process in which all grow. "2

Freire makes it clear that problem-posing education is revolutionary and

futuristic in character. "... it affirms men as beings who transcend themselves, who

move forward and look ahead, for whom immobility represents a fatal threat, for

whom looking at the past must only be a means of understanding more clearly what

and who they are so that they can more wisely build the future. "3

Freire is not merely an armchair philosopher but a radical who, having known

poverty and hunger and oppression first-hand, evolved his educational methods

while teaching illiterates in Latin America. Pedagogy of the Oppressed is not the

result of thought and study alone, but is rooted in concrete situations observed

during the course of his highly original and successful educative work. Freire is a

great lover of humanity and a seminal thinker whose influence may result in

fundamental changes in our educational system. Towards the end of his preface to

Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he says: "From these pages I hope at least the following

will endure: my trust in the people, and my faith in men and in the creation of a

world in which it will be easier to love. "4

We present here Chapter II of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a scathing criticism

of contemporary teacher-student relationships and an insightful call for change.

1. Ibid., p. 52.

2. Ibid:, p. 53.

3. Ibid., p. 57

4. Ibid., p. 19.

Page-493

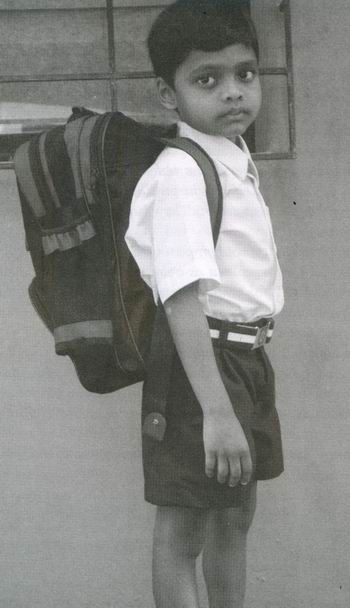

The burdened child, Photo EAVP, India, 2005

Page-494

A

careful analysis of the teacher-student relationship at any level, inside or

outside the school, reveals its fundamentally narrative character. This

relationship involves a narrating Subject (the teacher) and patient, listening

objects (the students). The contents, whether values or empirical dimensions of

reality, tend in the process of being narrated to become lifeless and petrified.

Education is suffering from narration sickness.

The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalized and predictable. Or else he expounds on a topic completely alien to the

existential experience of the students. His task is to "fill" the students with the

contents of his narration contents which are detached from reality, disconnected

from the totality that engendered them and could give them significance. Words are

emptied of their concreteness and become a hollow, alienated and alienating

verbosity.

The outstanding characteristic of this narrative education, then, is the sonority

of words, not their transforming power. "Four times four is sixteen; the capital of

Para is Belem." The student records, memorizes and repeats these phrases without

perceiving what four times four really means, or realizing the true significance of

"capital" in the affirmation "the capital of Para is Belem," that is, what Belem means

for Para and what Para means for Brazil.

Narration (with the teacher as narrator) leads the students to memorize

mechanically the narrated content. Worse still, it turns them into "containers", into

receptacles to be filled by the teacher. The more completely he fills the receptacles,

the better a teacher he is. The more meekly the receptacles permit themselves to be

filled, the better students they are.

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the

depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher

issues communiques and "makes deposits" which the students patiently receive,

memorize, and repeat. This is the "banking" concept of education, in which the

scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and

storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or

cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is men themselves who

are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this

(at best) misguided system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men

cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-

invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in

the world, with the world, and with each other.

Page-495

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those

who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know

nothing. Projecting an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the

ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry.

The teacher presents himself to his students as their necessary opposite; by

considering their ignorance absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students,

alienated like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as justifying

the teacher's existence but, unlike the slave, they never discover that they educate

the teacher.

The raison d'etre of libertarian education, on the other hand, lies in its drive

towards reconciliation. Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-

student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are

simultaneously teachers and students.

This solution is not (nor can it be) found in the banking concept. On the

contrary, banking education maintains and even stimulates the contradiction through

the following attitudes and practices, which mirror oppressive society as a whole:

1. The teacher teaches and the students are taught.

2. The teacher knows everything and the students know nothing.

3. The teacher thinks and the students are thought about.

4. The teacher talks and the students listen meekly.

5. The teacher disciplines and the students are disciplined.

6. The teacher chooses and enforces his choice, and the students comply.

7. The teacher acts and the students have the illusion of acting through the

action of the teacher.

8. The teacher chooses the program content, and the students (who were not L

consulted) adapt to it.

9. The teacher confuses the authority of knowledge with his own professional

authority, which he sets in opposition to the freedom of the students.

10. The teacher is the subject of the learning process, while the pupils are mere

objects.

It is not surprising that the banking concept of education regards men as

adaptable, manageable beings. The more students work at storing the deposits

entrusted to them, the less they develop the critical consciousness which would

result from their intervention in the world as transformers of that world. The more

Page-496

completely they accept the passive role imposed on them, the more they tend simply

to adapt to the world as it is and to the fragmented view of reality deposited in them.

The capacity of banking education to minimize or annul the students' creative

power and to stimulate their credulity serves the interests of the oppressors, who care

neither to have the world revealed nor to see it transformed. The oppressors use their

"humanitarianism" to preserve a profitable situation. Thus they react almost

instinctively against any experiment in education which stimulates the critical

faculties and is not content with a partial view of reality but is always seeking out

the ties which link one point to another and one problem to another.

Indeed, the interests of the oppressors lie in "changing the consciousness of the

oppressed, not the situation which oppresses them" (Simone de Beauvoir in La

Pensee de Droite Aujourd'hui) for the more the oppressed can be led to adapt to that

situation, the more easily they can be dominated. To achieve this end, the oppressors

use the banking concept of education in conjunction with a paternalistic social action

apparatus, within which the oppressed receive the euphemistic title of "welfare

recipients". They are treated as individual cases, as marginal men who deviate from

the general configuration of a "good, organized, and just" society. The oppressed are

regarded as the pathology of the healthy society, which must therefore adjust these

"incompetent and lazy" folk to its own patterns by changing their mentality. These

marginals need to be "integrated", "incorporated" into the healthy society that they

have "forsaken".

The truth is, however, that the oppressed are not marginals, are not men living

"outside" society. They have always been inside inside the structure which made

them "beings for others". The solution is not to "integrate" them into the structure

of oppression, but to transform that structure so that they can become "beings for

themselves". Such transformation, of course, would undermine the oppressors'

purposes; hence their utilization of the banking concept of education to avoid the

threat of student conscientization.

The banking approach to adult education, for example, will never propose to

students that they consider reality critically. It will deal instead with such vital

questions as whether Roger gave green grass to the goat, and insist upon the

importance of learning that, on the contrary, Roger gave green grass to the rabbit. The

"humanism" of the banking approach masks the effort to turn men into automatons

the very negation of their ontological vocation to be more fully human.

Those who use the banking approach, knowingly or unknowingly (for there are

innumerable well-intentioned bank-clerk teachers who do not realize that they are

Page-497

serving only to dehumanize), fail to perceive that the deposits themselves contain

contradictions about reality. But, sooner or later, these contradictions may lead

formerly passive students to turn against their domestication and the attempt to

domesticate reality. They may discover through existential experience that their

present way of life is irreconcilable with their vocation to become fully human. They

may perceive through their relations with reality that reality is really a process,

undergoing constant transformation. If men are searchers and their ontological

vocation is humanization, sooner or later they may perceive the contradiction in

which banking education seeks to maintain them, and then engage themselves in the

struggle for their liberation.

But the humanist, revolutionary educator cannot wait for this possibility to

materialize. From the outset, his efforts must coincide with those of the students to

engage in critical thinking and the quest for mutual humanization. His efforts must

be imbued with a profound trust in men and their creative power. To achieve this, he

must be a partner of the students in his relations with them.

The banking concept does not admit to such a partnership and necessarily

so. To resolve the teacher-student contradiction, to exchange the role of depositor,

prescriber, domesticator, for the role of student among students would be to under-

mine the power of oppression and to serve the cause of liberation.

Implicit in the banking concept is the assumption of a dichotomy between man

and the world: man is merely in the world, not with the world or with others; man is

spectator, not re-creator. In this view, man is not a conscious being (corpo consciente);

he is rather the possessor of a consciousness; an empty "mind" passively open to the

reception of deposits of reality from the world outside. For example, my desk, my

books, my coffee cup, all the objects before me as bits of the world which

surrounds me would be "inside" me, exactly as I am inside my study right now.

This view makes no distinction between being accessible to consciousness and

entering consciousness. The distinction, however, is essential: the objects which

surround me are simply accessible to my consciousness, not located within it. I am

aware of them, but they are not inside me.

It follows logically from the banking notion of consciousness that the

educator's role is to regulate the way the world "enters into" the students. His task

is to organize a process which already happens spontaneously, to "fill" the students

by making deposits of information which he considers constitute true knowledge.'

And since men "receive" the world as passive entities, education should make them

more passive still, and adapt them to the world. The educated man is the adapted

Page-498

man, because he is more "fit" for the world. Translated into practice, this concept is

well suited to the purposes of the oppressors, whose tranquillity rests on how well

men fit the world the oppressors have created, and how little they question it.

The more completely the majority adapt to the purposes which the dominant

minority prescribe for them (thereby depriving them of the right to their own

purposes), the more easily the minority can continue to prescribe. The theory and

practice of banking education serve this end quite efficiently. Verbalistic lessons,

reading requirements,2 the methods for evaluating "knowledge", the distance

between the teacher and the taught, the criteria for promotion: everything in this

ready-to-wear approach serves to obviate thinking.

The bank-clerk educator does not realize that there is no true security in his

hypertrophied role, that one must seek to live with others in solidarity. One cannot

impose oneself, nor even merely co-exist with one's students. Solidarity requires

true communication, and the concept by which such an educator is guided fears and

proscribes communication.

Yet only through communication can human life hold meaning. The teacher's

thinking is authenticated only by the authenticity of the students' thinking. The

teacher cannot think for his students, nor can he impose his thought on them.

Authentic thinking, thinking that is concerned about reality, does not take place in

ivory-tower isolation, but only in communication. If it is true that thought has

meaning only when generated by action upon the world, the subordination of

students to teachers becomes impossible.

Because banking education begins with a false understanding of men as

objects, it cannot promote the development of what From, in The Heart of Man,

calls "biophily", but instead produces its opposite: "necrophily".

While life is characterized by growth in a structured, functional manner, the

necrophilous person loves all that does not grow, all that is mechanical. The

necrophilous person is driven by the desire to transform the organic into the inorganic,

to approach life mechanically, as if all living persons were things.... Memory, rather

than experience; having, rather than being, is what counts. The necrophilous person

can relate to an object a flower or a person only if he possesses it; hence a threat

to his possession is a threat to himself; if he loses possession he loses contact with the

world.... He loves control, and in the act of controlling he kills life.

Oppression overwhelming control is necrophilic; it is nourished by love

of death, not life. The banking concept of education, which serves the interests of

Page-499

oppression, is also necrophilic. Based on a mechanistic, static, naturalistic,

spatialized view of consciousness, it transforms students into receiving objects. It

attempts to control thinking and action, leads men to adjust to the world, and inhibits

their creative power.

When their efforts to act responsibly are frustrated, when they find themselves

unable to use their faculties, men suffer. "This suffering due to impotence is rooted

in the very fact that the human equilibrium has been disturbed", says From. But

the inability to act which causes men's anguish also causes them to reject their

impotence, by attempting

...to restore [their] capacity to act. But can [they], and how? One way is to submit to

and identify with a person or group having power. By this symbolic participation in

another person's life, [men have] the illusion of acting, when in reality [they] only

submit to and become apart of those who act.

Populist manifestations perhaps best exemplify this type of behaviour by the

oppressed, who, by identifying with charismatic leaders, come to feel that they

themselves are active and effective. The rebellion they express as they emerge in the

historical process is motivated by that desire to act effectively. The dominant elites

consider the remedy to be more domination and repression, carried out in the name

of freedom, order and social peace (the peace of the elites, that is). Thus they can

condemn logically, from their point of view "the violence of a strike by

workers and [can] call upon the state in the same breath to use violence in putting

down the strike" (Niebuhr's Moral Man and Immoral Society).

Education as the exercise of domination stimulates the credulity of students,

with the ideological intent (often not perceived by educators) of indoctrinating them

to adapt to the world of oppression. This accusation is not made in the naive hope that

the dominant elites will thereby simply abandon the practice. Its objective is to call

the attention of true humanists to the fact that they cannot use the methods of banking

education in the pursuit of liberation, as they would only negate that pursuit itself.

Nor may a revolutionary society inherit these methods from an oppressor society. The

revolutionary society which practises banking education is either misguided or

mistrustful of men. In either event, it is threatened by the spectre of reaction.

Unfortunately, those who espouse the cause of liberation are themselves

surrounded and influenced by the climate which generates the banking concept, and

often do not perceive its true significance or its dehumanizing power. Paradoxically,

Page-500

then, they utilize this very instrument of alienation in what they consider an effort to

liberate. Indeed, some "revolutionaries" brand as innocents, dreamers, or even

reactionaries those who would challenge this educational practice. But one does not

liberate men by alienating them. Authentic liberation the process of humanization

is not another "deposit" to be made in men. Liberation is a praxis: the action and

reflection of men upon their world in order to transform it. Those truly committed to

the cause of liberation can accept neither the mechanistic concept of consciousness

as an empty vessel to be filled, nor the use of banking methods of domination

(propaganda, slogans deposits) in the name of liberation.

The truly committed must reject the banking concept in its entirety, adopting

instead a concept of men as conscious beings, and consciousness as consciousness

directed towards the world. They must abandon the educational goal of deposit-

making and replace it with the posing of the problems of men in their relations with

the world. "Problem-posing" education, responding to the essence of consciousness

intentionality rejects communiques and embodies communication. It

epitomizes the special characteristic of consciousness: being conscious of, not only as

intent on objects but as turned in upon itself in a Jasperian "split" consciousness

as consciousness of consciousness.

Page-501

Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferrals of information. It is a learning situation in which the cognizable object (far from being the

end of the cognitive act) intermediates the cognitive actors teacher on the one hand

and students on the other. Accordingly, the practice of problem-posing education first

of all demands a resolution of the teacher-student contradiction. Dialogical relations

indispensable to the capacity of cognitive actors to cooperate in perceiving the

same cognizable object are otherwise impossible.

Indeed, problem-posing education, breaking the vertical patterns characteristic of

banking education, can fulfill its function of being the practice of freedom only if it

can overcome the above contradiction. Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students

and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student

with students-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one

who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in their turn while being

taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow. In

this process, arguments based on "authority" are no longer valid; in order to function,

authority must be on the side of freedom, not against it. Here, no one teaches another,

nor is anyone self-taught. Men teach each other, mediated by the world, by the

cognizable objects which in banking education are "owned" by the teacher.

The banking concept (with its tendency to dichotomize everything) distinguishes

two stages in the action of the educator. During the first, he cognizes a cognizable

object while he prepares his lessons in his study or his laboratory; during the second,

he expounds to his students on that object. The students are not called upon to know,

but to memorize the contents narrated by the teacher. Nor do the students practise any

act of cognition, since the object towards which that act should be directed is the

property of the teacher rather than a medium evoking the critical reflection of both

teacher and students. Hence in the name of the "preservation of culture and

knowledge" we have a system which achieves neither true knowledge nor true culture.

The problem-posing method does not dichotomize the activity of the teacher-

student: he is not "cognitive" at one point and "narrative" at another. He is always

"cognitive", whether preparing a project or engaging in dialogue with the students.

He does not regard cognizable objects as his private property, but as the object of

reflection by himself and the students. In this way, the problem-posing educator

constantly re-forms his reflections in the reflection of the students. The students

no longer docile listeners are now critical co-investigators in dialogue with the

teacher. The teacher presents the material to the students for their consideration, and

re-examines his earlier considerations as the students express their own. The role of

Page-502

the problem-posing educator is to create, together with the students, the conditions

under which knowledge at the level of the doxa is superseded by true knowledge, at

the level of the logos.

Whereas banking education anaesthetizes and inhibits creative power,

problem-posing education involves a constant unveiling of reality. The former

attempts to maintain the submersion of consciousness; the latter strives for the

emergence of consciousness and critical intervention in reality.

Students, as they are increasingly faced with problems relating to themselves

in the world and with the world, will feel increasingly challenged and obliged to

respond to that challenge. Because they apprehend the challenge as interrelated to

other problems within a total context, not as a theoretical question, the resulting

comprehension tends to be increasingly critical and thus constantly less alienated.

Their response to the challenge evokes new challenges, followed by new under-

standings; and gradually the students come to regard themselves as committed.

Education as the practice of freedom as opposed to education as the practice

of domination denies that man is abstract, isolated, independent, and unattached

to the world; it also denies that the world exists as a reality apart from men.

Authentic reflection considers neither abstract man nor the world without men, but

men in their relations with the world. In these relations consciousness and world are

simultaneous: consciousness neither precedes the world nor follows it. "La

conscience et le monde sont formes d'un meme coup; exterieur par essence a la

conscience, le monde est, par essence, relatif a elle",3 writes Sartre. In one of our

culture circles in Chile, the group was discussing (based on a codification) the

anthropological concept of culture. In the midst of the discussion, a peasant who by

banking standards was completely ignorant said: "Now I see that without man there

is no world." When the educator responded: "Let's say, for the sake of argument, that

all the men on earth were to die, but that the earth itself remained, together with

trees, birds, animals, rivers, seas, the stars... wouldn't all this be a world?" "Oh no,"

the peasant replied emphatically. "There would be no one to say: 'This is a world'."

The peasant wished to express the idea that there would be lacking the

consciousness of the world which necessarily implies the world of consciousness.

"I" cannot exist without a "not I". In turn, the "not I" depends on that existence. The

world which brings consciousness into existence becomes the world o/that

consciousness. Hence the previously cited affirmation of Sartre: "La conscience et

Ie monde sont formes d'un meme coup."

As men, simultaneously reflecting on themselves and on the world, increase the

Page-503

scope of their perception, they begin to direct their observations towards previously

inconspicuous phenomena. Husseri writes:

In perception properly so-called, as an explicit awareness

[Gewahren], I am turned

towards the object, to the paper, for instance. I apprehend it as being this here and now.

The apprehension is a singling out, every object having a background in experience.

Around and about the paper lie books, pencils, ink-well and so forth, and these in a

certain sense are also "perceived", perceptually there, in the "field of intuition"; but

whilst I was turned towards the paper there was no turning in their direction, nor any

apprehending of them, not even in a secondary sense. They appeared and yet were not

singled out, were not posited on their own account. Every perception of a thing has

such a zone of background intuitions or background awareness, if "intuiting" already

includes the state of being turned towards, and this also is a "conscious experience",

or more briefly a "consciousness of all indeed that in point of fact lies in the co-

perceived objective background.

That which had existed objectively but had not been perceived in its deeper

implications (if indeed it was perceived at all) begins to "stand out", assuming the

character of a problem and therefore of challenge. Thus, men begin to single out

elements from their "background awarenesses" and to reflect upon them. These

elements are now objects of men's consideration, and, as such, objects of their action

and cognition.

In problem-posing education, men develop their power to perceive critically

the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves; they

come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in

transformation. Although the dialectical relations of men with the world exist

independently of how these relations are perceived (or whether or not they are

perceived at all), it is also true that the form of action men adopt is to a large extent

a function of how they perceive themselves in the world. Hence, the teacher-student

and the students-teachers reflect simultaneously on themselves and the world

without dichotomizing this reflection from action, and thus establish an authentic

form of thought and action.

Once again, the two educational concepts and practices under analysis come

into conflict. Banking education (for obvious reasons) attempts, by mythicizing

reality, to conceal certain facts which explain the way men exist in the world;

problem-posing education sets itself the task of de-mythologizing. Banking

education resists dialogue; problem-posing education regards dialogue as

Page-504

indispensable to the act of cognition which unveils reality. Banking education treats

students as objects of assistance; problem-posing education makes them critical'

thinkers. Banking education inhibits creativity and domesticates (although it cannot

completely destroy) the intentionality of consciousness by isolating consciousness

from the world, thereby denying men their ontological and historical vocation of

becoming more fully human. Problem-posing education bases itself on creativity

and stimulates true reflection and action upon reality, thereby responding to the

vocation of men as beings who are authentic only when engaged in inquiry and

creative transformation. In sum: banking theory and practice, as immobilizing and

fixating forces, fail to acknowledge men as historical beings; problem-posing theory

and practice take man's historicity as their starting point.

Problem-posing education affirms men as beings in the process of becoming

as unfinished, uncompleted beings in and with a likewise unfinished reality. Indeed,

in contrast to other animals who are unfinished, but not historical, men know

themselves to be unfinished; they are aware of their incompleteness. In this

incompleteness and this awareness lie the very roots of education as an exclusively

human manifestation. The unfinished character of men and the transformational

character of reality necessitate that education be an ongoing activity.

Education is thus constantly remade in the praxis. In order to be, it must

become. Its "duration" (in the Bergsonian meaning of the word) is found in the

interplay of the opposites permanence and change. The banking method emphasizes

permanence and becomes reactionary; problem-posing education which accepts

neither a "well-behaved" present nor a predetermined future roots itself in the

dynamic present and becomes revolutionary.

Problem-posing education is revolutionary futurity. Hence it is prophetic (and,

as such, hopeful), and so corresponds to the historical nature of man. Thus, it affirms

men as beings who transcend themselves, who move forward and look ahead, for

whom immobility represents a fatal threat, for whom looking at the past must only

be a means of understanding more clearly what and who they are so that they can

more wisely build the future. Hence, it identifies with the movement which engages

men as beings aware of their incompleteness an historical movement which has

its point of departure, its subjects and its objective.

The point of departure of the movement lies in men themselves. But since men

do not exist apart from the world, apart from reality, the movement must begin with

the men-world relationship. Accordingly, the point of departure must always be with

men in the "here and now", which constitutes the situation within which they are

Page-505

submerged, from which they emerge, and in which they intervene. Only by starting

from this situation which determines their perception of it can they begin to

move. To do this authentically they must perceive their state not as fated and

unalterable, but merely as limiting and therefore challenging.

Whereas the banking method directly or indirectly reinforces men's fatalistic

perception of their situation, the problem-posing method presents this very situation

to them as a problem. As the situation becomes the object of their cognition, the

naive or magical perception which produced their fatalism gives way to perception

which is able to perceive itself even as it perceives reality, and can thus be critically

objective about that reality.

A deepened consciousness of their situation leads men to apprehend that

situation as an historical reality susceptible of transformation. Resignation gives way

to the drive for transformation and inquiry, over which men feel themselves in

control. If men, as historical beings necessarily engaged with other men in a

movement of inquiry, did not control that movement, it would be (and is) a violation

of men's humanity. Any situation in which some men prevent others from engaging

in the process of inquiry is one of violence. The means used are not important; to

alienate men from their own decision-making is to change them into objects.

This movement of inquiry must be directed towards humanization man's

historical vocation. The pursuit of full humanity, however, cannot be carried out in

isolation or individualism, but only in fellowship and solidarity; therefore it cannot

unfold in the antagonistic relations between oppressors and oppressed. No one can be

authentically human while he prevents others from being so. The attempt to be more

human, individualistically, leads to having more, egotistically: a form of dehumanization. Not that it is not fundamental to have in order to be human. Precisely because

it is necessary, some men's having must not be allowed to constitute an obstacle to

others' having, to consolidate the power of the former to crush the latter.

Problem-posing education, as a humanist and liberating praxis, posits as

fundamental that men subjected to domination must fight for their emancipation. To

that end, it enables teachers and students to become subjects of the educational

process by overcoming authoritarianism and an alienating intellectualism; it also

enables men to overcome their false perception of reality. The world no longer

something to be described with deceptive words becomes the object of that trans-

forming action by men which results in their humanization.

Problem-posing education does not and cannot serve the interests of the

oppressor. No oppressive order could permit the oppressed to begin to question:

Page-506

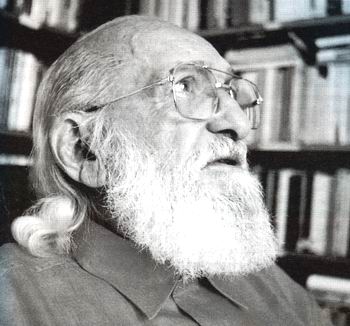

Paulo Freire, courtesy Paulo Freire Institute

Why? While only a revolutionary society can carry out this education in systematic

terms, the revolutionary leaders need not take full power before they can employ the

method. In the revolutionary process, the leaders cannot utilize the banking method

as an interim measure, justified on grounds of expediency, with the intention of later

behaving in a genuinely revolutionary fashion. They must be revolutionary that

is to say, dialogical from the outset.

From Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed

(Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985), pp. 45-59.

Page-507

References

1. This concept corresponds to what Sartre calls the "digestive" or "nutritive" concept of education,

in which knowledge is "fed" by the teacher to the students to "fill them

out". See Jean-Paul Sartre,

"Une idee fondamentale de la phenomenologie de Husserl: l' intentionalite", Situations

I .

2. For example, some teachers specify in their reading lists that a book should be read from pages

10 to 15 and do this to "help" their students!

3. "Consciousness and the world are formed at the same time. The world, being by essence external

to consciousness, is by essence relative to it."

Biography

Paulo Freire was born in 1921 in Recife, Brazil, the centre of one of the poorest and most

underdeveloped areas in the Third World. As the economic crisis in 1929 in the United States began

to affect Brazil, the precarious stability of Freire's middle-class family gave way and he found

himself sharing the plight of the "wretched of the earth". He came to know the gnawing pangs of

hunger and fell behind in school because of the listlessness it produced. It also led him at the age

of eleven to make a vow to dedicate his life to the struggle against hunger, so that other children

would not have to know the agony he was then experiencing. As he grew up, it became clear to him

that one of the main reasons for chronic poverty and the "culture of silence" around it was the

educational system. As he studied and experienced the world of education, he applied the insights

of many contemporary thinkers and philosophers, such as Sartre, Mounier, Erich Fromm, Louis

Althusser, Martin Luther King, Che Guevera, Unamuno and Marcuse. But he arrived at his own

prescription for education, which seeks to respond to the concrete realities of Latin America.

In 1959, Freire presented his philosophy of education in his doctoral dissertation at the

University of Recife. Later, he worked as Professor of the History and Philosophy of Education in

the same university. His radical methods were widely used in literacy campaigns throughout north-

east Brazil. But the old order began to consider him a threat, and he was jailed immediately after

the military coup in 1964. Released seventy days later and encouraged to leave the country, Freire

went to Chile, where he spent five years working with UNESCO and the Chilean Institute for

Agrarian Reform in programmes of adult education. He also acted as consultant at Harvard

University's School of Education, and worked in close association with a number of groups

engaged in new educational experiments in rural and urban areas.

Although Freire began his career as a Brazilian educator, in the course of a few years his thought

and work spread from north-east Brazil to the entire continent, and made a profound impact not just

in the field of education but on the overall struggle for national development. Today, the work of

Paulo Freire is being gradually acknowledged even in the United States.

Freire has written many articles in Portuguese and Spanish, and his first book, Educacao como

Pratica da Liberdade, was published in Brazil in 1967. In 1970, Cultural Action for Freedom

appeared as the English translation. In this book, he pointed out that learning is not a matter of

Page-508

memorization and repetition, but of reflecting critically on the very processes of reading and

writing, and on the profound significance of language itself. In this book he outlined the principles'

which underlay his highly original and spectacularly successful method of teaching literacy, which

sought to challenge the basic concepts that dominated education and culture in the slums and

villages of Latin America. Pedagogy of the Oppressed was first published in Great Britain by Sheed

and Ward in 1972.

Many people today are writing and thinking about education in radical terms. Ivan D. Illich for

instance, in Deschooling Society argues that school is one of the major means by which the status

quo is preserved. He points out that school is not only inefficient in terms of education, but also

profoundly divisive. Everett Reiner, in his book School is Dead argues that for most people schools

are "institutional props for privilege". He sees as an urgent priority a consideration of alternatives

in regard to the content, organization and finance of education and in regard to the very concept of

education itself, its nature and possible functions in a future society. UNESCO has spearheaded a

radical programme of education in its publication Learning to Be. There are other important and

^ radical trends in the educational field today. Against this background Paulo Freire can be

considered one of those radical thinkers whose influence may ultimately bring about fundamental

changes in our educational system. Freire combines a compassion for the wretched of the earth with

intellectual and practical confidence and personal humility.

Page-509 |